In a previous post Roger Perkins cited an online article by Dr. James White about the pre-existence of Jesus. Here is the link and a portion of that material.

Click here to read article from AOMIN.org http://vintage.aomin.org/The_Pre_Existence_of_Christ.html

________________________________

The Pre-existence of Christ

In Scripture, Patristics and Creed

by James White

Introduction

Our modern world is decidedly confused. On the one hand, the rationalistic, humanistic viewpoint dominates within our public education system. We are now taught to question the validity of anything that can be called "supernatural." The very idea that someone might believe in miracles, revelation, etc., is opened up to direct ridicule. At the same time, in a direct reaction against this kind of dry humanism, many people are fleeing for refuge into every kind of spiritistic group imaginable. "Channeling" (a fancy way of saying a spirit medium) is very popular, and the Eastern ideas of reincarnation and mysticism are drawing converts from every walk of life.

In the midst of all of this confusion we find the Bible, continuing to proclaim the timeless message of Jesus Christ. Yet even the Lord Jesus has come in for modern "updating" in many men's writings. After a century of "searching for the historical Jesus" men (hopefully) have discovered that outside of the inspired writings of the apostles in the New Testament, we will not find much information on who Jesus was. Indeed, unless we see that it is illogical and irrational to reject the Scriptures for what they claim to be

(1) we will never have much to say to our world.

Today it is normal for "Christian" theologians to de-emphasize the doctrinal aspects of the Person of Jesus Christ. Since rationalism and naturalism are the modes of the day, it is unpopular to deal with the clear Biblical teaching of the deity of the Lord Jesus and his pre-existence. The person who looks to the Bible, however, has little choice in the matter - the doctrine is clearly stated both in the Gospels as well as the epistles, and indeed it is implicit in most of the New Testament.

One cannot easily disassociate the doctrine of the pre-existence of Christ from that of his deity, as they are part and parcel of the same teaching. An in-depth discussion of the deity of Christ is outside of the realm of this paper, and it will be assumed that an understanding of the main elements of this doctrine are shared with the reader.

(2)

This discussion will be limited to the focal passages found in the New Testament that deal with the pre-existence of the Lord Jesus. For our purposes these are as follows: John 1:1-3, Colossians 1:15-17, and Philippians 2:5-7. Each of these passages have much in common, as we shall see in our examination of them, both in an exegetical understanding, as well as in patristic interpretation.

It will be relevant to a discussion of the early Church's views to discuss the order of writing of the books which contain our primary data on the pre-existence of Christ. Generally, the Pauline epistles are dated anywhere from the late 40's to the late 60's of the first century. The majority of scholarship sees Paul's writings preceding John's by quite some time, and there is general agreement concerning the order of Paul's letters and their place in history.

(3) The question of the exact date of John's gospel, however, is not so easily resolved. Merril C. Tenney

(4) notes that modern estimates range from 45 to beyond 100 A.D. Part of the problem can be found in the fact that during what might be called the "hypercritical" period of the last century, it became quite popular to deny the Johanine authorship of the Gospel of John, and, due to its high Christology (which the rationalists assumed had to be a mythological invention of the early Church) place it at least into the second century. Modern textual finds (such as the famous P75) have demolished any ideas of a second-century date for John, and today the dates normally fall between A.D. 85 and 95.

(5) What is very important to notice about the fact of the early (i.e., non-second century dating) is that the Christology of John is, therefore, no different than that of the early Church as the book was written during the same time period! Indeed, there is no way for there to have been sufficient time for such "myths" to have evolved, and, it is not logical to think that John would have written about certain events that could be proven false by living witnesses! With these facts in mind, we can move on to the actual exegesis of these passages.

Exegesis of Principal Passages

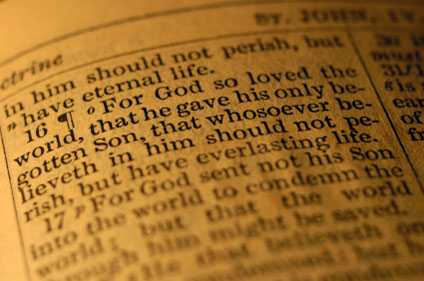

The Prologue of John (1:1-18) is unique in Biblical literature. It is clear that the main point of John is not the person of God. His emphasis is the identity of the Word. The Logos is the central figure of the work, and the teaching of the passage is that the Logos is intricately involved with the creation of the universe. The pre-existence of the Logos is clearly stated and assumed throughout the prologue.

Much has been said concerning the origin of the term logos. Philo

(6) used the term, yet the logos of Philo is simply an impersonal manifestation of the Wisdom of God. John's usage of the term may indeed borrow from Philo (especially if John wrote the Gospel while in Ephesus, as the Greeks would be able to understand the term), but he goes far beyond anything Philo dreamed of. Rather than a pantheistic, impersonal divine emanation, the Logos of John is a personal, eternal being who is not simply a part of creation, but is rather the Creator himself.

The first verse itself must be examined to be understood. Transliterated into Greek the verse reads: En arche en ho logos, kai ho logos en pros ton theon, kai theos en ho logos. The verse breaks down into three clauses, each being vital to the whole. The first thing to notice is the fact that the imperfect form of eimi is used throughout the prologue in reference to the Logos. This tense, attached to the phrase "en arche" is timeless - i.e., as far back as one wishes to push the "beginning" the Word is already in existence. This is seen, for example, in the translation of the New English Bible which renders it, "When all things began, the Word already was." Today's English Version puts it, "Before the world was created, the Word already existed...." Hence, the first phrase clearly presents the eternality of the Word and hence his pre-existence.

The second phrase presents the inter-personal relationship of the Logos and God. The Greek phrase pros, translated "with," refers to the existence of communication and fellowship between the Logos and theos.

(7)The word was used to describe being "face to face" with another. Now, unless John had added the final phrase ("and the Word was God") there would have been a problem here, as the first phrase clearly presents the Logos as eternal, while the second demonstrates his distinct personality. This would create polytheism without the final phrase's emendation. At the same time, this second clause ends any chance of Sabellianism's success.

The final phrase, kai theos en ho logos, presents a syntactical arrangement in which the term theos is emphasized. At the same time, the sentence is copulative, and the presence of the article with logossimply sets it out as the subject of the sentence. Much has been said concerning the lack of the article with theos

(8) but -that discussion is beyond the scope of this paper. Basically, the construction 1) avoids modalism (i.e., the Word is not said to be completely co-extensive with theos) and 2) teaches that the Word has the same nature as God (a point that Paul will reiterate in Philippians).

Verse 3 links the eternality of the Word with creatorship. "Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made." John here is intent on separating the Logos from the realm of the created - he started in the very first phrase by asserting his timeless existence and continues here by attributing to the Logos all of creation, an item that will reappear in Colossians. The only possible way to interpret these verses is to see the Logos as an eternal being who created all things.

The prologue continues by identifying the Logos with the person of Jesus Christ in 1:14. It is interesting to note that John very carefully differentiates between the Word in his absolute nature and all other things. When the eternal Word is in view, John uses en. When created things are being discussed (such as John in 1:6), the aorist egeneto is found. However, when we come to the time event of 1:14 (i.e., the incarnation), John switches from the timeless en to the aorist egeneto - the Word became flesh at a point in time in history.

Finally, in 1:18(9), John seals the case by calling Jesus the "only-begotten God," or, more accurately, the "unique God"(10) who reveals the Father, who "exegetes"(11) God to man.

These verses with which John begins his gospel are meant, in my opinion, to form an "interpretive window" through which the reader is meant to look at the words that follow. One must constantly keep the Logos in the back of the mind when interpreting the words and actions of Jesus.

(12) Much of what Christ says must be understood in this light to even make much sense! His unique relationship with the Father is intelligible only in the light of his eternal preexistence with him.

<trunc.

Endnotes

1) 2 Timothy 3:16-17, 2 Peter 1:20-21.

2) This writer sees the following passages as directly ascribing to Jesus Christ the term God: Isaiah 9:6 (Hebrew: Elohim), John 1:1 (Greek: theos), 1:18, 20:28, Acts 20:28 (depending on text), Romans 9:5, Titus 2:13, Hebrews 1:8, 2 Peter 1:1 and (possibly) I John 5:20. Interestingly, in reference to Titus 2:13 (and 2 Peter 1:1 - both similar syntactical constructions) Chrysostom ("Homily lV on Philippians in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers volume 13) pg.207 clearly understood the implications of the syntax of Titus 2:13, and bases part of his polemic against the Arians on the application of theos to Christ. See also A. T. Robertson, The Minister and His Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1977), pgs. 61-68.

3) F. F. Bruce Paul Apostle of the Heart Set Free (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1977) p. 475 places the epistles of Paul in the following order: Galatians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Romans, Philippians, Colossians,

Ephesians, Philemon, 1 & 2 Timothy, Titus with Galatians at 48 A.D., Colossians and Philippians in 60-62 A.D., and Paul's death in approximately 65 A.D. This is almost identical to A. T. Robertson's (" Paul the Apostle" in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1956) vol. 3:2265 - 2266) order of writing, with the exception of Galatians, which Robertson places just before Romans. See also Ralph Martin, "Colossians and Philemon" in The New Century Bible Commentary, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1983) pg. 30 on the dating of Colossians.

4) Merril C. Tenney, "John" in The Expositor's Bible Commentary, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1981) vol. 9, pp.9-10.

5) Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1985) vol.1:721-724 gives a good argument for Johanine authorship, and dates it before 100 A.D. A.T.Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1932) vol.5:1 dates John at A.D. 90. James lverach, "John the Apostle" in The lnternational Standard Bible Encyclopedia, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1956) vol. 3:1721-1722 also dates John at the end of the first century.

6) G.L. Prestige, God in Patristic Thought, (London: SPCK, 1952), pp. 124,141. Ralph Martin, "Colossians and Philemon" in The New Century Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1973) pg. 58.

7) A. T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research(Nashville: Broadman Press, 1934) pp. 625f. See discussion in A. T. Robertson, The Divinity of Christ in the Gospel of John (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1976) pp. 34-46.

8) See F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1983) p. 31, or Leon Morris, The Gospel According to John, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1971) pg. 77 for a discussion of some of the issues involved in the translation of this phrase. Most noteably, the New World Translation of the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society mistranslates the phrase as "the Word was a god."

9) On the text of 3 John 1:18 and the superiority of the reading theos over huios, see Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the New Testament (New York: United Bible Societies, 1975) p.198, A. T. Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament, 5:17. For citation of manuscripts, see the UBS text, 3rd ed. corrected, p. 322.

10) For the true meaning of monogenes see J. H. Moulton and George Milligan, The Vocabulary of the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1935) pp. 416-417.

11) Greek: exegesato, to lead out, bring forth, make known, explain.

12) For an interesting discussion of the relationship of the Prologue to the rest of John, see John A. T. Robinson, Twelve More New Testament Studies (London: SCM Press, 1984) pp. 65-76.

13) Philip B. Harner, The I Am Sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of John, (Fortress Press, 1970).

14) Ralph Martin, "Colossians and Philemon" pp. 55 -57; F. F. Bruce, Paul Apostle of the Heart Set Freepp.418ff. For further information on the passage as well as exegesis, see John Calvin, Calvin's Commentaries vol. 21:151-152.

15) See Wilhelm Michaelis, "Prototokos" in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1982) vol. 6:872ff.

16) See M. Tsevat, "Bekhor" in Theological Dictionary of the old Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1975) vol.2:121ff. On prototokos see entry in Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature edited by Gingrich and Danker, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979) p. 726.

17) J. B. Lightfoot, St. Paul's Epistles to the Colossians and Philemon (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1959) pp. 150-151. See also pp. 151-153 on the extent of ta panta.

18) For other views and discussion on Colossians 1:15-17 in a theological setting, see Donald Guthrie,New Testament Theology (Inter-Varsity Press: USA, 1981) pp.344-352; George Eldon Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1974) pp. 419-421.

19) Donald Guthrie, New Testament Theology pp. 342- 352; George Eldon Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament pp. 419-421; Henry Alford, New Testament for English Readers (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1983) pp. 1262-1264; Kenneth Wuest, "Philippians" in Word Studies in the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1981) pp. 62-65;J. B. Lightfoot, St. Paul's Epistles to the Philipians (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1953) p. 137.

20) See discussion under patristic interpretation.

21) Ibid.

22) Both the Authorized Version and the New International Version see that the term kenosis is always used metaphorically by Paul hence, the translation "to make of no repute" or to "make himself nothing." It is never used by Paul of a literal "emptying."

23) J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (New York: Longman Inc., 1981) pp. 87, 91..cw 9.

24) Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, ed., The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1981) vol. 1:546.

25) For the text of the Nicene Creed, see J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Creeds (New York: Longman Inc., 1981), pp.215-216 and Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1985) vol. 1:27-28.

26) Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, vol. 1:30.

27) John Chrysostom, "Homilies on St. John" in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Philip Schaff, ed. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1980) vol. 14:8.

28) Chrysostom, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 14:12.

29) Chrysostom, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 14:18. His entire exegesis found in pages 10-19 is excellent.

30) Chrysostom, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 13:271.

31) Chrysostom, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 13:207-208.

32) Athanasius, "Four Discourses Against the Arians" in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (series II) ed. by Philip Schaff (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, 1980) vol. 5:409.

33) Athanasius, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 4:329.

34) Athanasius, "Statement of Faith" in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 5:85.

35) Athanasius, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 5:375. See also 5:382.

36) Augustine, "Homilies on the Gospel of John" in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers series I, edited by Philip Schaff, vol. 7:7-13. Augustine also connected the idea of pre-existence with the absolute usage ofego eimi at John 8:21-25 in vol. 7:218-219.

37) Augustine, "Enchiridion," in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 3:249.

38) See also Augustine, "On Faith and Creed" in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 3.322-323, 329.

39) Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, vol. 3:619-620.